Fiji is a common law jurisdiction and a constitutional democracy that guarantees its citizens the right to a clean and healthy environment.

Fiji's Constitution and environmental laws also guarantee the rights of those concerned by any development that may have a significant impact on the environment to participate in the decision-making process.

In this bulletin we consider how those who are concerned may exercise their rights to participate in decisions that will ultimately assist Fiji, its government and people better safeguard the environment, ocean and natural resources that are so vital for its economy and well being.

Section 40 of Fiji’s Constitution provides that:

Every person has the right to a clean and healthy environment, which includes the right to have the natural world protected for the benefit of present and future generations through legislative and other measures.

The right to a clean and healthy environment may be limited by law or by administrative action taken in accordance with law. But any decision to limit any section 40 right should follow a participatory and lawful decision making process that both enables the views of Fiji citizens to be heard and for those views and any relevant concerns to be taken into account.

Fiji’s Environment Management Act, 2005 (EMA) assists with good decision making by requiring environmental impact assessments (EIAs) for any major development. The EIA process and reports should thoroughly assess the impacts of a development to enable the decision-maker to decide whether the development should be permitted or not and if it is permitted on what conditions.

EIAs are therefore an essential tool to assist decision-makers to meet EMA’s objective to ensure that development:

Meets the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs, and implies using resources to improve the quality of human life within their carrying capacity.

However, the EIA process also promotes and enables public consultation on the environmental, social or cultural issues of the development. For this reason, and for others discussed below, the EIA process promotes good governance and decision-making for Fiji’s environment, its oceans and natural resources.

It is in the best interests of Fiji, its government, its people, and its various industries from tourism to agriculture that good decisions are made that impact Fiji’s environment and natural resources. To be a good and informed decision the decision-making process must be participatory, transparent and lawful. The process should take into account the benefit of development and balance this against the environmental, social and cultural effects of the development as well as Fiji’s international commitments to safeguard its environment, oceans and natural resources.

This means that good decision-making is not just the Fiji government’s responsibility because to enable better decision-making in relation to Fiji’s natural resources it is necessary for people to be interested in the environmental, social and cultural effects of any major development and to participate in the decision-making process itself.

A good example that illustrates the importance of involvement in the decision making process relates to the dredging of the Sigatoka River. At present, there are concerns being raised in relation to the decision that has been taken to dredge the river, for example see article here.

While the concerns that are expressed in the above linked article about the dredging of the Sigatoka river seem well founded and are based on expert opinion relating to the environmental impacts of river dredging, it is important to bear in mind that once an administrative decision is taken by any government in favour of the development it is extremely hard to reverse the decision or its effects. This may be because the development itself has taken place and the natural resources removed or adversely affected, or it is because a commercial entity has committed to the investment of large sums of money on the basis of the decision. Further, regardless of the rights or wrongs of the decision experience in this area has shown that decision-makers rarely reverse earlier decisions despite always having the power to do so.

This does not mean that a legal challenge against a poorly made decision is not possible, and in fact Fiji’s common law system is underpinned by the administrative law right to challenge before the High Court any administrative/executive decision that is not taken in accordance with the law or the common law principles of due process/natural justice. But these legal challenges are technical, and must be able to demonstrate a failure to follow the law or due process, they must also be brought within 3 months of the date of the decision, provide only a discretionary remedy, as well as being expensive and time consuming.

The Environment Management Act or EMA is supposed to provide an alternative route of challenge to decisions in favour of development within 21 days of the decision by way of application to Fiji’s Environmental Tribunal. Unfortunately though, as yet and 10 years after EMA came into force, this Environmental Tribunal has not been established, presumably due to a lack of resources. [Editorial note: Please note that the Environment Tribunal has now been established, and our firm recently (August 2019) filed an appeal on behalf of concerned citizens relating to the approval of an EIA. Our case was listed as the 5th case of 2019].

While legal challenges to environmental decisions may be undertaken after specific legal advice has pinpointed the questions that are open to legal challenge, this route must be viewed as a last resort. This means the better option for those concerned is to become involved in the decision-making process itself and influence the final decision through well founded argument. This involvement should focus on providing the best information on the environmental, social and cultural impacts of the proposed development to the decision-makers as well as illustrating how the development could impact Fiji's international commitments to its environment, oceans and natural resources. [Editorial note: This situation may have recently changed as we have become aware of an appeal lodged with the Environment Tribunal, but at this stage have not seen any rulings or decisions from it nor any publicity around its establishment]. [Further note: we can confirm that this situation has changed as the Environment Tribunal has been established.]

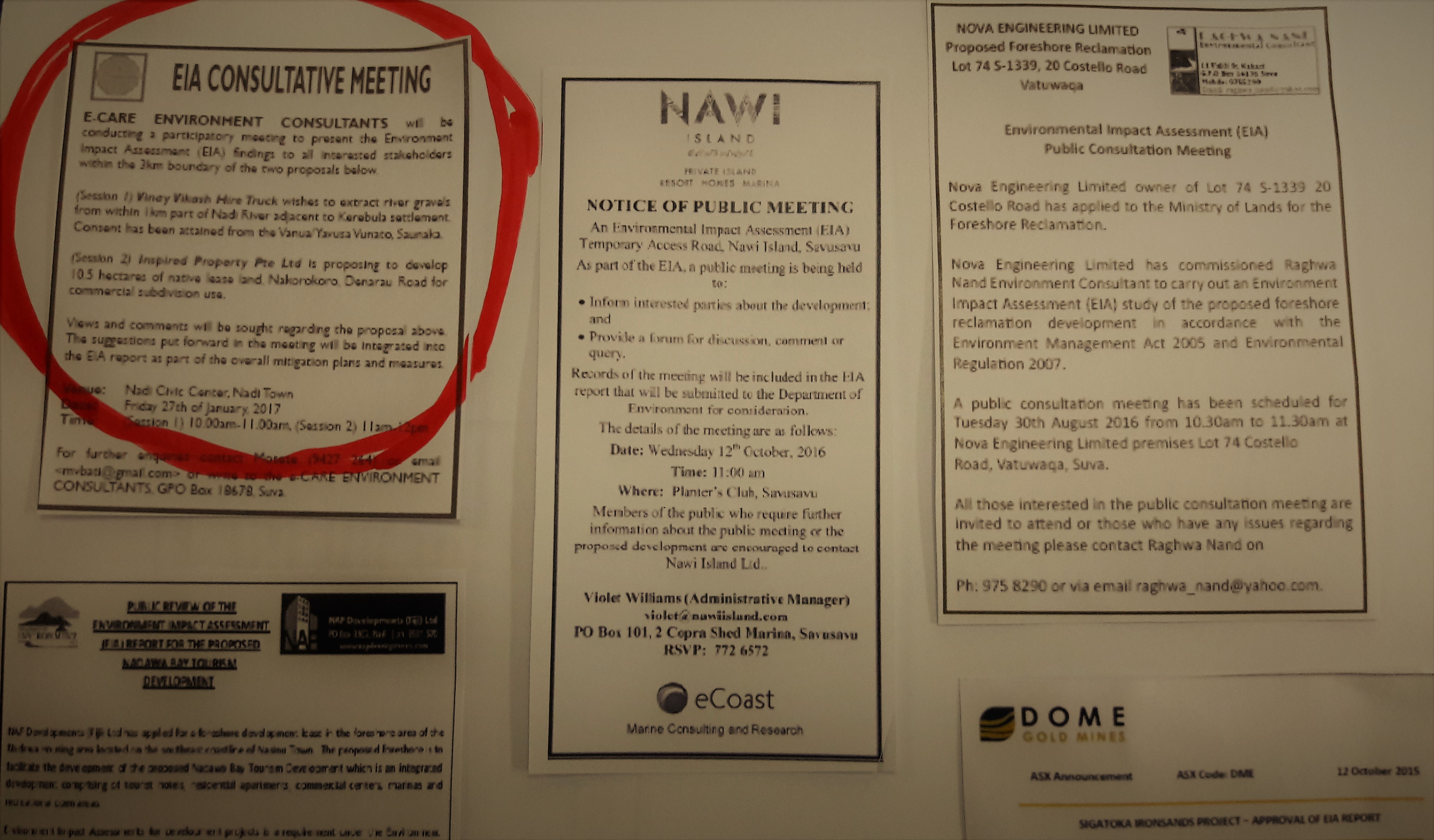

Within EMA’s EIA process there are a number of formal opportunities where public consultation is or may be required or information can be obtained, and this includes:

- During the EIA process the developer must hold at least one public consultation

- After the EIA report has been prepared the developer must conduct at least one public review meeting close to the proposed development site

- Once the EIA report is approved the Department of Environment must retain a copy that can be inspected and copied at the Department of Environment during normal office hours.

While not every development will require an EIA process and report, any development that is likely to have significant environmental impact and certain developments must have an EIA. This includes developments that will involve:

- Mangrove removal/destruction

- Coastal land reclamation

- Mining and mineral exploration

- Commercial and industrial development

- Dredging

- Logging and sawmilling operations

- Quarries and gravel extraction

- The development of a hotel or tourist resort

- Residential subdivision for more than 10 lots

Further, EIAs will be required for any development that could cause serious environmental or public health harm like coastal or beach erosion, pollution of a water resource, pollution or degradation of agricultural land, alteration of natural processes of the sea, introduce harmful pollutants to the air, jeopardise protected or endangered species, harm or destroy protected areas, lead to depletion of non-renewable natural resources etc. [For a full list see Schedule 2, Parts 1 and 2 of EMA].

It should be noted that any development that requires an EIA pursuant to EMA that does not undertake an EIA will be unlawful development. Unlawful development is a serious criminal offence that can result in penalties of up to 10 years in prison and/or a fine of $750,000.00.

Following the EIA process, the decision whether to approve the EIA rests with the Department of Environment (in the case of Schedule 2 Part 1 to EMA developments), or the approving authority. The Department of Environment or approving authority can approve the development proposal with or without conditions, not approve the development proposal or recommend additional studies.

Whether the development finally proceeds will depend on the developer obtaining all the other necessary legal approvals from government agencies.

Of all the ways that concerned persons may become involved, the public consultations are likely to provide the best opportunities for them to have their say. This should be done by preparing for and attending any public consultation that the proponent of the development holds, and by providing comment and/or written submissions relating to relevant issues or concerns that should be taken into account as part of the EIA.

The sort of issues or concerns that may be legitimately raised in relation to any development proposal include, but are not limited to:

- Environmental impacts of the development - including any impact on Fiji's oceans, fisheries, mangroves or other natural resources

- Social impacts of the development

- Economic impacts of the development - this could include economic fishing rights

- Cultural impacts of the development including any rights that may be lost or affected by the development - this will have particular significance in the case of development that could affect fishing rights over qoliqoli areas.

- Particular concerns relating to the development site for example is it important culturally, biologically or unique for some other reason?

- Public health and safety concerns

- Any conflicts that could arise in relation to competing interests for the site

- How any adverse impacts of the development could be reduced

- How any proposed use of the site could conflict with another use of the site or its resources.

- How the development could contradict or negatively impact any international commitments that Fiji has made.

Please note this is not an exhaustive or prescriptive list and anyone concerned with any particular development should voice concerns that affect or are particular to their interests and how they or their community could be impacted by the development. Remember at this stage, the information that is provided is to assist the EIA and the decision-maker make the best possible decision in accordance with the law.

If there are concerns regarding the EIA, from either a process perspective or from a technical perspective then pursuant to section 17 of EMA, the DOE is required to maintain an Environmental Register that must record all “prescribed matters”, a definition which includes EIAs, and the DOE is required to provide access to the EIA to any person who asks for it. We are aware of at least one recent situation where the DOE refused such access but relented when the law firm involved in that matter referred to section 54 of EMA which enables any person to: "institute an action in a court to compel any Ministry, department or statutory authority to perform any duty imposed on it by this Act."

Further, once the EIA report is submitted either the DOE or other approving authority must provide public notice of the report, setting out where the development is proposed, the nature of the development and setting out how the public may comment on the report within a 28 day time frame.

Ultimately, the EIA report should be a comprehensive assessment of the environmental, social and cultural impacts of the proposed development as well as considering ways to mitigate any adverse effects. The EIA report must comply with EMA’s requirements and a good, well considered, and well prepared EIA will assist the decision-maker.

The public consultation that is required to review the EIA report enables interested and concerned parties to check the quality of the EIA report before any final decision is taken by the decision-maker who may approve or reject the development proposal, or approve it with conditions aimed at mitigating any environmental, social or cultural impacts.

There is no doubt that when the final decision on whether to approve a development that could cause significant environmental impact the key influencing factor for the decision maker will be the EIA. However, this does not mean that the ultimate decision maker can or should blindly follow the EIA report as he or she must also consider the nature and scope of the development, how significant the environmental impacts will be, whether any measures to mitigate the impact are feasible and any public concerns about the development. This means that public concerns should always be voiced clearly and consistently where there is any concern because these will assist the final decision and indicate why public participation is a crucial factor in all decisions that impact Fiji’s environment or natural resources.

Conclusions

Getting involved in decision-making is not easy and may require travel to the development site or area which could be in more remote areas and may involve seeking expert legal, technical or scientific advice. Further, the published notices that notify the public of EIA meetings where there is a right to participate are not always easy to spot and require careful and regular review of the notices section in Fiji’s national newspapers. These notices could be shared around relevant organisations to increase their awareness when they are published.

While it is in the interests of all of Fiji’s citizens that good decisions are made, there is currently a weakness in the system of checks and balances because the Environmental Tribunal contemplated by EMA is still not established. [Editorial Note: this situation has now changed as the Environment Tribunal is now established and accepts appeals pursuant to the EMA]. Once established this Environmental Tribunal will better enable challenges to any decision to be made within 21 days of the decision and therefore strengthen Fiji's environmental decision-making. As things stand, the only route of legal challenge is to fall back on Fiji’s administrative law system and bring a challenge before the High Court which for the reasons discussed is not always practical.

Public concern related to the impacts of any development is always a factor that should be taken into account by Fiji’s decision makers and is also essential to the proper functioning of Fiji’s constitutional democracy. Fiji’s citizens are entitled to exercise their lawful rights to consult within the EIA process, review the EIA report and voice any concerns through other legitimate means.

The voicing of concerns should not be seen as conflicting with the decision-maker or government agency because ultimately it is in everyone’s best interests that the best possible and most informed decision is made that fairly balances the environmental, social and cultural impacts against the benefits of the development.

Further information may be obtained from: The Fiji Environmental Law Association [www.fela.org.fj]

The Fiji Environmental Law Association has produced detailed Fact Sheets to EIAs and participation in decision-making as well as other important subjects and these can be found here

The Fiji Environmental Law Association has also published presentations made on a variety of areas of environmental law that can be found here

Please note:

This legal bulletin is provided for general information purposes only and it is not, and should not be relied on as, legal advice.

This legal bulletin was amended in November 2018 to record the apparent establishment of the Environment Tribunal.